Why the Historical Evidence for the Resurrection Is Stronger than the Records of Alexander the Great

When historians study the ancient world, they rarely have video footage, audio recordings, or eyewitness interviews. Instead, they work with surviving manuscripts, inscriptions, letters, official records, and later historical accounts. These sources are evaluated according to several key questions. How close in time was the source written to the event it describes. Was the writer an eyewitness, or did they have access to eyewitness testimony. How many independent sources confirm the report. Is there evidence that the story changed or developed over time. What motives or biases might the author have had, and do those biases explain or distort the narrative. These principles apply equally whether historians study the Gospels or the life of Alexander the Great.

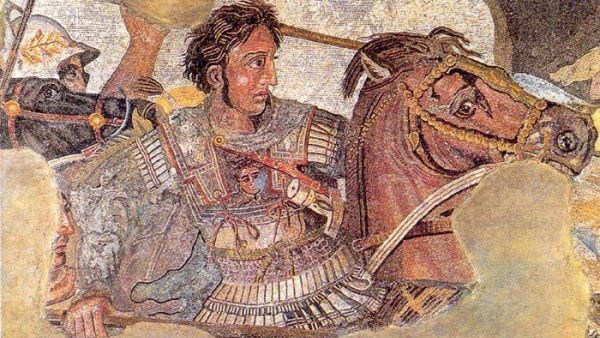

Alexander the Great is one of the most famous figures in history, yet the surviving written accounts about him were not produced during his lifetime. Our two major ancient biographies come from Plutarch and Arrian, both writing around four hundred years after Alexander’s death. They themselves relied on earlier sources, many of which are now lost. This means layers of retelling, copying, and interpretation stand between modern historians and the original events. While historians still treat these sources as valuable, they do so with caution because long gaps in time increase the risk of legend, embellishment, and national or political storytelling. The farther away a document is from the events it describes, the greater the chance that memory, myth, or cultural agendas have shaped the narrative.

By contrast, the accounts of the resurrection of Jesus were written much closer to the time the events reportedly occurred. Most scholars agree that the New Testament letters, especially Paul’s letters, were written within twenty to thirty years of the crucifixion. In 1 Corinthians 15 Paul records an early Christian creed that speaks of Jesus dying, being buried, rising again, and appearing to witnesses. Almost all historians recognize that this creed predates Paul’s letter and likely originated within only a few years of the crucifixion. In historical terms that level of immediacy is extraordinary. It means that claims about the resurrection were not slowly developed over centuries but were being proclaimed by people who lived in the same generation as the reported events.

The Gospels were also written within the lifetime of eyewitnesses. Even if scholars debate the exact dating, they acknowledge that many people who personally knew Jesus, His followers, and His enemies were still alive when these texts circulated. That matters historically. If the writers had invented or distorted the story, critics could challenge them directly. The resurrection was proclaimed publicly in the very city where Jesus was crucified, among those who saw the events unfold. The early Christian movement did not treat the resurrection as a symbolic myth but as a public, historical claim subject to examination.

Some argue that the Gospel writers were biased because they were believers. But historians do not dismiss a source simply because the author believes in what he is writing about. All ancient historians had perspectives, loyalties, and motives. Greek and Roman historians frequently wrote to honor rulers, defend national pride, or shape political identity. The real question is whether an author’s commitment forces the text to contradict known facts or produce distortions that serve an agenda. In the case of the New Testament, the disciples had every worldly reason not to invent a resurrection story. Their preaching led to persecution, imprisonment, and in many cases martyrdom. They did not gain political power or wealth. Instead, they suffered for a claim they insisted was true.

In the study of Alexander the Great, historians recognize that the long gap between event and document increases the possibility of heroic exaggeration. Stories can be reshaped through legend, nationalism, and political mythmaking as generations pass. The further the memory travels away from the eyewitness generation, the easier it becomes for historical truth to blend with cultural storytelling. By contrast, the resurrection proclamation emerged immediately, among those who could confirm or deny it. It was not a slow mythological buildup across centuries, but a bold public claim grounded in witnesses who testified at personal cost.

When judged simply by historical criteria such as time of writing, proximity to events, manuscript preservation, plurality of witnesses, and resistance to corruption by later legend, the resurrection documents stand much closer to the events than our surviving biographies of Alexander the Great.

The point is not that secular historians unanimously accept the resurrection as fact. The point is that the historical record surrounding Jesus is unusually early, multiply attested, and grounded in a community that was convinced enough to stake their lives on what they claimed to have seen. In historical terms this makes the resurrection account uniquely significant. It is not a distant legend emerging centuries later. It is a testimony rooted in immediate memory, preserved in documents that stand far nearer to the events than many accounts we otherwise accept as reliable history.

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!